Canvas Business Models Analysis

The notion of Business Model has been used since the 1960s [83] and has received a lot of attention since the 1990s [84]. It has been approached from different fields such as e-business, information systems, computer science, strategy or management [85]. The business model concept offers managers a coherent way to consider their options in uncertain, fast-moving and unpredictable environments [86]. Many definitions can be found in literature focusing the approach on business strategy [87] useful for our research purpose. Amongst the most cited in the literature is the one given by Osterwalder and Pigneur [88] who consider that business models describe the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers and captures value.

Innovations can be regarded as products, services or processes which were not available before, or which differ significantly from existing products and services [89]. Performance measurement systems are required to control and plan innovation [89]. Business model innovation describes the design process for giving birth to a fairly new business model on the market, which is accompanied by an adjustment of the value proposition and/or the value constellation and aims at generating or securing a sustainable competitive advantage [90].

Many tools which assist companies to define, evaluate or plan the implementation of business models are found in literature [84,91,92]. Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas has become the most famous framework for this purpose between researchers and academics [87,93]. This framework is a visual chart composed of nine charts describing a firm’s or product’s value proposition, customers, and finances. It was resumed afterwards with a deeper analysis of the value proposition chart, for which it was developed the Value Proposition Canvas [94]. Some researchers have modified a few parts of the framework for various different purposes [95]. In fact, even the developers of the Business Model Canvas presented a modified framework specially designed to analyze the business model of non-profit organizations which they also recommend for public administrations [88] as when analyzing public services, the public value should also be taken in account [23]. The main difference between the Non-Profit Business Model Canvas and the original Canvas is that the first one includes two additional parameters, “Social and Environmental Profits” and “Social and Environmental Cost” (Figure 1). These new parameters are used to collect a number of not purely economic values that are important when making decisions that affect the society.

Figure 1. Non-Profit Business Model Canvas [88].

Performance measurement is key in business strategy [52] and it is also needed in the field of business model analysis [54]. However, although some have been developed for this purpose [96], there is actually a gap in literature relating to performance measurement of collaborative business models [97,98].

2.5. Application of Business Models Analysis to Smart Cities

The term business model is commonly used in social innovation environments [91] and it has also been used to analyze companies that employ technology to create and capture value [99]. Some approaches have also been carried out in analyzing business models in IoT driven environments through the development of specific frameworks for this purpose [100,101,102,103]. Therefore, it is not surprising that the concept has also been linked to smart cities [83,104,105,106,107,108]. When applied to the urban context, innovative technologies leverage a disruption in the management of public services so it is necessary to design innovative business models [109].

Nevertheless, the few researchers and practitioners that have used theoretical frameworks to analyze business models in smart cities applied the traditional Canvas [107,110] or created new frameworks specifically developed for this environment [36]. A paper describing a framework specifically designed to analyze business models in smart cities can be found in the literature; it uses the concepts of control and public value in order to take into account the intangible factors of the smart cities [7,111]. The same author has also developed a method to evaluate business models in smart cities [35].

3. Methodology

The objective of our work is to develop a new method for characterizing and benchmarking business models in smart cities. These kinds of frameworks are useful to try to understand how things work [112]. The research work has been developed using the constructive method. This methodology aims at solving managerial problems in business organizations through the construction of models, diagrams and plans useful to both industry practitioners and academics [113]. The process of using the constructive approach is made up of the following six steps, which may vary in order from case to case [114]:

- Choosing a relevant practical problem with research potential

- Obtaining pre-understanding of the topic

- Constructing a solution idea

- Assessing that the solution works

- Showing theoretical connections and research contribution of the solution

- Evaluating the scope and applicability of the solution

The constructive research steps are matched with suitable research methods and data so that the methodology reveals different angles of the research problem with a heterogeneous combination of complementary methods [114]. In our case, we have used several methodologies to conduct our research: content analysis, in-depth interviews, and case study. The complete process of the research work is illustrated in Table 1.

We analyzed research literature in the field which constitutes a content analysis method. Content analysis is a research technique which intends to be objective, systematic and quantitative in the study of the content of communications [115]. Through literature we identified the main frameworks for business model analysis and then we selected the one we considered more appropriate for smart cities, the Non Profit Business Model Canvas. Based on the selected framework and using the literature, we developed a method to evaluate business models in smart cities. This method is the main contribution of this paper.

Afterwards, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 11 experts. The interviewees were chosen through case selection. This type of selection is used when the objective is a depth and richness of information, but not the amount nor standardization. The total number of participants is determined by saturation of categories, whereby the number of participants is restricted to units of analysis that provide novel material [116]. Interviews were conducted with local politicians (two interviewees), business managers (four interviewees), and researchers specialized in business models or public management (five interviewees). The interviewees selected represent the roles of the triple helix of innovation [117] and they all have knowledge about business models and/or smart cities (their names, organization and positions of the interviewed are available in the following note [118]). Interviews lasted an average of 60 min. In-depth interviews are a widely used qualitative method in exploratory and social research [119]. When they are semi-structured, interviews allow flexibility, as topic lists do not need to be followed religiously and can be modified depending on the expertise or the issues raised during the conversation [120].

The experts were asked about the importance and objectives of analyzing business models in smart cities, their opinion about the existing frameworks to analyze business models, the parameters to be measured in the methodology to be developed, etc. They analyzed our methodology to evaluate business models in smart cities and then they gave some suggestions. A total of 10 interviewees considered appropriate the method we describe in this paper and only one recommended developing a different tool. We modified our first draft of the method in order to address their suggestions.

To assess our research and develop measures for a diverse array of sectors, we decided to choose two public services from different sectors, both operating with smart technologies: waste and street lighting management systems. We introduced two case studies since multiple-case studies provide a more solid foundation for theory building [123]. We analyzed the business models of these two case studies using the Business Model Canvas with the information collected observing how services are performing, public information available in the CKAN Open Data repository and additional information owned by the Municipality. The interviewees also gave values to the parameters related to both public services.

4. Results

This section is divided in three parts. First, the methodology development process to evaluate business models in smart cities is described. Second, the methodology is applied to the case study of the waste management system of the city of Santander. Third, a new application of the methodology is described in order to demonstrate that it may be applied to every use case, this time it is the street lighting infrastructure of Santander.

4.1. Description of the Evaluation Tool for Business Model Analysis in Smart Cities

The 11 experts interviewed expressed the desirability of developing a methodology for evaluating the business models of the public services in the smart cities. New technologies applied to urban management are opening up new possibilities for economic sustainability for cities and respondents perceive that a methodology to analyze and compare the possible business models would be useful for public administrations and companies, as well as for the research community.

When analyzing the business models implemented in public services, we have taken into account the point of view of the aggregation of actors, as seven respondents recommended. The local government is the main stakeholder responsible for the provision of municipal utilities, but other players in the ecosystem often participate too, such the case of a concessionaire or even proactive citizens are a couple of examples. This justifies that the business model from the point of view of the aggregation of all involved stakeholders as service providers has been take into consideration.

We developed the methodology we found most appropriate to evaluate business models in smart cities. It was also approved by 10 of the 11 respondents, who also provided some recommendations that we have applied afterwards. This paper introduces the resulting method (Table 2). The system assesses six out of the 11 parameters of Non-Profit Business Model Canvas which exhibit obvious outcomes and thus are feasible to be compared among different business models. Each parameter is evaluated on scale in which the negative figures refer to detrimental aspects for the smart city, and those positive refer to beneficial aspects. In the evaluation process, values are assigned in response to a total of 29 questions related to specific needs of each of the 6 parameters. These questions become qualitative indicators that combine objective and subjective measures.

The period taken as a reference has to be agreed before the assessment by those responsible for implementing this methodology. In the case that the service is provided on the basis of a private management model, it is usual, in terms of fixing the analysis period, to extend it to the duration of the public tender. Other reference periods are also possible, for example, the shelf life of the equipment to be invested in or the duration of its amortization.

The Business Model Evaluation Tool for Business Analysis in Smart Cities allows those who want to apply the method to benchmark the different business models to be assessed. For example, the valuator can make a comparison, both between the business model of the smart service to be implemented and the public service provided with traditional systems, as well as between different business models potentially implementable with smart technologies. The first example would assess the appropriateness of replacing a traditional public service business model with a smart technology one; the second example would help to choose the most appropriate new business model for the smart city, among the existing possibilities.

The six assessable parameters are the following:

- (a)

- Cost Structure: This parameter of the Business Model Canvas refers to the costs involved in operating the product or service, including investment in machinery, labor, raw materials, etc. For this evaluation we have created two variables:(a.i.) “Amount of costs that this product/service will generate for the city and the citizens”, which we consider the most relevant part of the parameter and allows taking into account whether an increase in costs or net savings in the reference period occurs. It is scored as follows:

- (−4): The service provided with smart technologies has 50% higher cost than the service provided by the traditional systems.

- (−3): The service provided with smart technology is more than 20% and up to 50% more expensive than the service provided by traditional systems.

- (−2): The service provided with smart technology is over 5% and up to 20% more expensive than the service provided by the traditional systems.

- (−1): The smart service provided technology costs between 0% and 5% more than the service provided with the traditional systems.

- (0): The service is provided with smart technologies has the same cost than the service provided with the traditional systems.

- (+1): The service provided with smart technologies will cost between 0% and 5% less than the service provided by traditional systems.

- (+2): The service provided with smart technology has a lower cost, ranging from 5% to 20% less than the service provided with traditional systems.

- (+3): The service provided with smart technology has a lower cost, which ranges from 20% to 50% less than the service provided with traditional systems.

- (+4): The service provided with smart technology has lower cost, being 50% cheaper or more than the service provided with traditional systems.

(a.ii.) “Diversification of cost sources”. We believe it is an aspect to take into account because the greater the diversification, the lower the risk for the city, so we assign a numeric value as follows:- (−1): It means that the sources are less diversified than in the service provided with traditional systems.

- (0): It is equivalent to the same diversification in the service provided with traditional systems.

- (+1): There is more diversification than in the service provided with traditional systems.

- (b)

- Revenue Streams: The Business Model Canvas describes this parameter as the revenues generated by the product or service, and in our method we start from the perspective of the evaluation between the business models to be compared. To evaluate this parameter, we have created two variables:(b.i.) “Amount of costs that this product/service will generate for the city and citizens”, which we consider the most relevant parameter and therefore is measured as follows:

- (−4): The service provided with smart technologies generates revenues 50% lower than the service provided with traditional systems.

- (−3): The service provided with smart technologies generates revenues between 20% and 50% lower than the service provided with traditional systems.

- (−2): The service provided with smart technologies has generated revenues between 5% and 20% lower than the service provided with traditional systems.

- (−1): The service provided with smart technologies generated revenues between 0% and 5% lower than the service provided with traditional systems.

- (0): The service provided with smart technologies generates revenues equivalent to the service provided with traditional systems.

- (+1): The service provided with smart technologies generates revenues between 0% and 5% higher than the service provided with traditional systems.

- (+2): The service provided with smart technology generates higher revenues, ranging from 5% to 20% more than the service provided with traditional systems.

- (+3): The service provided with smart technology generates higher revenues, ranging from 20% to 50% more than the service provided with traditional systems.

- (+4): The service provided with smart technology generates revenues over 50% higher than the service provided with traditional systems.

(b.ii.) “Diversification of sources of revenues”. We believe it is an aspect to consider as greater diversification brings less risk to the city. We propose a numeric value like this:- (−1): Applied to sources less diversified than in the traditional system.

- (0): Equivalent to the same diversification in the traditional system.

- (+1): Means that there is more diversification than in the traditional system.

- (c)

- Social and Environmental Costs: This parameter does not exist in the Business Model Canvas but it does in the Non-Profit Business Model Canvas. It refers to non-economic aspects of the business model that are harmful to the intelligent city. In general, these aspects are often the same in every city in the world, but municipalities have different priorities about which of them are more or less important. Therefore, we believe that the appropriate reference to assign values is the strategic plan of the city because the strategic objectives are evident on it. The assessment of social and environmental costs is made taking into account whether the business model analyzed adversely affects the strategic objectives of the city. For example, in the Santander case study we have taken the Santander Strategic Plan 2020 [124] and selected five strategic dimensions of the future vision of the city. Each dimension receives a value depending on how the business model affects that dimension according to the following assessment:

- (−1): It means that the( business model affects each strategic objective very negatively.

- (−0.5): To be assigned if the business model partially affects each strategic objective.

- (0): When it does not affect the strategic objective.

- (d)

- Social and Environmental Benefits: Just like the previous one, this parameter only exists in the Non-Profit Business Model Canvas. It refers to non-financial aspects of the business model that are beneficial for the smart city. The assignment of numerical parameter values is done by assessing how the business model analyzed contributes to the strategic objectives defined in the strategic plan of the city. In the case study we have taken the five strategic dimensions of the Strategic Plan of Santander 2020 and assigned values of 0 if the business model does not contribute to achieving this objective, 0.5 if it contributes a little, and 1 if it helps a lot.

- (e)

- Value Proposition: This parameter makes explicit how Organizations are creating value for customers. In our methodology we have developed five questions that help assess to what extent is the business model analyzed valuable. Each question can be answered with 0 points (negative answer to that question), 0.5 points (partially positive response) or 1 point (fully positive response). These questions have been created by us, but are based on others presented in the book that introduced the Value Proposition Canvas.

- (f)

- Customer Segments: This parameter shows for how many citizens the business model is potentially applicable, beneficial or harmful. There are five positive and five negative values that are adding or subtracting fractions of 1 point until it exceeds 50% of the population, which we consider the top as it is clearly beneficial for whole the population.

In benchmarking business models, the six parameters can be compared either separately or jointly. In order to facilitate comparisons of business models as a whole, we have designed a formula that calculates a single value for the entire business model. This formula arises from the answers given to the Evaluation Tool and its objective is to make business model benchmarking easier. We called it Value of the Business Model (VBM). This value is calculated as follows:

VBM = (CE + RE − SEC + SEB + VP)CS

VBM = Value of the Business Model

CE = Cost Structure

RE = Revenue Streams

SEC = Social and Environmental Costs

SEB = Social and Environmental Benefits

VP = Value Proposition

CS = Customers Segment

4.2. Use Case: The Waste Management System of the City of Santander

The Santander waste management solution relies on the IoT infrastructure to collect real time information which enables to analyze huge data amounts aiming at supporting the decision making process. We analyzed the business model of the new waste management system taking as a reference point the comparison with the traditional model that has been applied so far (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of the business models of the conventional waste management service and the one integrating IoT infrastructure.

Then, the business model linked to the new system (Table 4) is compared with the one which has been operating so far:

- There is a small increase in financial costs for the service provider as it must invest to cover the costs of technology. However, the Cost Structure is lower because the total management costs are clearly smaller in the long term as the last public tender for this service showed. In other words, as the new technologies allow a more efficient management, the costs of the first public tender of the service that demanded the use of IoT technologies was tendered for a value of less than 20% with respect to the previous one, which was managed conventionally. As we take the point of view of aggregation actors, 2 points are allocated in this sub-parameter. Another 0.5 points are added due to the diversification of sources of costs as the service provider benefits from reduced fuel costs, human resources and other factors.

- The Revenue Streams do not change at all so 2 points are assigned in this parameter.

- We believe that as Social and Environmental Costs, 0.5 points should be considered -due to the potential small reduction of employees in the service can damage social cohesion.

- The Social and Environmental Benefits add 1 point because these innovative technologies put Santander on the map as a city where the knowledge economy and productive innovation predominate; 0.5 points for the generation of talent for hiring highly qualified professionals to manage ICTs; 0.5 points for improving the quality of service for all citizens as it promotes social cohesion; and 1 point for the improvement in environmental sustainability and accessibility as lower consumption of CO2 and less traffic disruption are clear benefits of optimized vehicle routes.

- We give 0.5 points in the Value Proposition parameter because the necessity of improving the waste management service is permanent for city halls and citizens, nevertheless we do not consider it a problematic issue at this time; 0.5 points because people are always interested in improving waste management but do not claim massively for it; another 0.5 points because traffic congestion and environmental improvements are upgrades in the quality of life; 0.5 points because the service quality is slightly better than the former one; 1 point because the 20% reduction of the total cost of the service is an important saving for municipal budgets in such kind of projects.

- We added 5 points in the Customers parameter because the new service constitutes an important upgrade for all citizens.

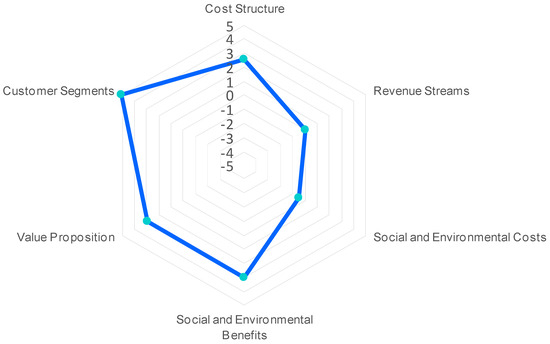

The result of the application of this methodology can be easily visualized when captured in a radar chart. It is depicted in Figure 2.

In case we want to get a pooled analysis to compare among various business models, we can apply the formula expressed below:

VBM = (CE + RE − SEC + SEB + VP) × CS

VBM = (2.5 + 0 − 0.5 + 3 + 3) × 5 = 45

4.3. Use Case: The Street Lighting Service of Santander

The Santander street lighting use case has been used as an example to validate the Evaluation Tool. The business model of the new street lighting system has been compared with the conventional model that has been applied so far (Table 5).

Table 5. Comparison of the business models of the conventional street lighting infrastructure and the system integrating ICT infrastructure.

The evaluation of the business model of the new street lighting in relation to the one that has been developed so far is described in the following bullets (Table 6):

- An important initial investment is required and assumed by the concessionaire. However, the net Cost Structure is lower in the long term as the last public tender for this service showed. In other words, the first public tender of the service that demanded the use of LED and innovative ICT was tendered for a lower value with respect to the previous one, which was managed conventionally. As we take the point of view of aggregation actors, thus we give 2 points in this parameter.

- The Revenue Streams do not change at all so 0 points are assigned in this parameter.

- We believe that no Social and Environmental Costs stand out (0 points).

- A few factors are included between the Social and Environmental Benefits: 0.5 points because these innovative technologies contribute to put Santander on the map as a city where the knowledge economy and productive innovation predominate; 0.5 points for the generation of talent for hiring highly qualified professionals to manage ICTs; and 1 point for the sustainability supported by the reduction of energy consumption.

- In the Value Proposition parameter, it is given: 0.5 points because it is always necessary to improve an important municipal service like this; 0.5 points because citizens are always interested on improving the service, even if they do not claim massively for it; and 1 point because the reduction of the total cost of the service is an important saving for municipal budgets in such kind of projects.

- We added 5 points in the Customers parameter because the new service constitutes an important upgrade for all citizens, at least in terms of public budget.

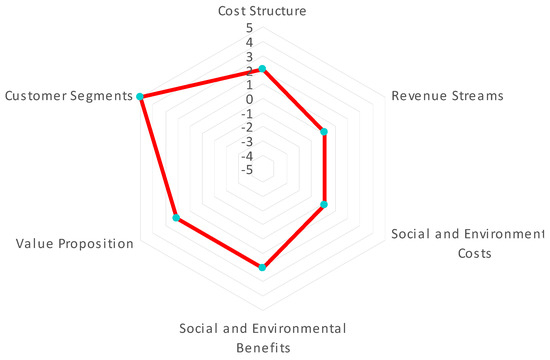

The result of the application of the methodology can be easily visualized when captured in a radar chart. It can be seen in the following graph (Figure 3).

In case we want to get a pooled analysis to compare among various business models, we can apply the formula expressed below:

VBM = (CE + RE − SEC + SEB + VP) × CS

VBM = (2 + 0 + 0 + 3 + 3) × 5 = 40

5. Discussion

The creation of a methodology to assess the business models of public services can be useful for actors involved in urban management and social innovation in smart cities, including governments, businesses and citizens.

Nowadays, the Business Model Canvas is the most used framework for business model analysis among entrepreneurs, businessmen and researchers. Its simplicity and the well designed and executed communications actions are two key parts of its success. It seems reasonable to predict that a method based on the most used framework will have greater reception than an unknown system. In fact, several researchers have published amendments to the Canvas in order to analyze business models of specific activities. The methodology proposed in this research paper, the Business Model Evaluation Tool for Smart Cities, maintains the premises of simplicity and being based on the most used method. Being based in a widely adopted framework is an advantage related to the other existing method for evaluating business models in smart cities [35] because all the users of the Business Model Canvas will get familiar with this method quickly and easily. The Evaluation Tool also has a couple of important features in common with the existing method: both are based on qualitative indicators and take into account intangible factors that are key to evaluate smart cities’ performance.

The Evaluation Tool introduced is a simple methodology that involves answering 29 simple questions using numerical values. It is a system with an organized structure that leads to measurable conclusions. As a specific methodology to be agreed upon by those responsible for assessing the different business models to be compared, it gives transparency to the process. In addition, its quick implementation allows evaluating and comparing two or more business models and making strategic decisions swiftly.

As described in the analysis of literature, the best-known frameworks to analyze business models focus on creating revenues and do not take into account other important values for society. Among these non-economic values are improving the citizen’s quality of life or the care for the environment which are a priority for the government. The method we propose overcomes this obstacle by relying on the Non-Profit Business Model Canvas, an extension of the Business Model Canvas that takes social and environmental values into account.

The point of view of the aggregation has been taken as several members of the smart city ecosystem may take part in the design and implementation of public services. In the case studies described in this research paper, the aggregation of actors involved are the City Hall, responsible for providing the service in the most convenient manner; the company hired to manage the service; and the local university, which in these cases has been a fundamental part of the service design. In other business models, other different stakeholders are also involved, such as citizens who, for example, could provide essential information to manage the public service. Therefore, in order to analyze the business model, it is appropriate to take the viewpoint of the aggregation, even if some stakeholders are, in turn, part of the provision of service and customers thereof.

Evaluators may compare the results of the six parameters of the business models analyzed in the methodology or the entire model as well. In order to measure each business model as a whole, we have also created a formula to obtain a single numerical value model. This fact, which we call Value of the Business Model (VBM), is easily comparable with the value of other business models. As the VBM contains both objective and subjective indicators, it could be slightly biased, as it actually happens with many existing performance indicators in social sciences. In our method it specially happens when benchmarking cities with different strategic objectives as the 10 questions related to social and environmental costs and benefits change according to the strategic objectives of the city, so that the business models are consistent with the strategic plan of the city. In these specific situations, benchmarking VBM values which start from different questions could drive to slightly biased results. Nevertheless, it is still a method more accurate, transparent and fair than taking a guess.

Cities pose different objectives and pursue various positions; therefore, the aspects to be measured cannot be the same in all of them. The adaptation of the method to the strategic plan of the city promotes strategic planning and allows any user profile to use it. Obviously, previously there must be a public strategic plan of the city. In the event that it does not exist or is not public, evaluators must first agree on the strategic objectives to use as reference.

In governance, most decisions are debatable. But even having an unavoidable part of subjectivity, decision making through a transparent methodology leads to fairer decisions and strengthens citizens’ confidence. Assessing the adequacy of a business model to the strategic plan of the city involves a subjective evaluation, and furthermore other parameters of the Evaluation Tool are also up to a certain point subjective. In fact, Cost Structure may be objective in the case of concessions of public services with a fixed price, but in other cases the value of this parameter is based on forecasts and, therefore, when using the Evaluation Tool a subjective factor is introduced. The grading of the parameters of Revenue Stream and Customer Segment also depend on forecasts which can be more or less successful, like it happens in all the businesses. As for the parameters of Social and Environmental Costs and Benefits, as well as the Value Proposition, their subjective nature emanates from the personal opinions of each member of the valuation panel. Some of the 29 questions that compose the Evaluation Tool include objective and subjective measures, prevailing the last one of them because the future performance of a business model obviously holds a heavy subjective component. In this sense, it is reasonable to suppose that a panel formed by diverse profiles should enrich the quality of the valuation and reduce its subjectivity. Despite the existence of a certain amount of subjectivity in the evaluation of business models with the Evaluation Tool, its use should remain useful for those who are faced with choosing a business model because it facilitates analysis and decision-making taking into account various perspectives, and enhances accountability and transparency. Business is not an exact science and, thus, both technical forecast and instinct are necessary. Evaluation tools may show results slightly biased and can be focused on selfish indicators, but they have their manifest advantages with respect to making at a guess.

As all members of the smart city ecosystem are potential developers of services and drivers of innovation, they are also potential users of the Evaluation Tool. This methodology meets this need as the profile of people who can use this methodology is heterogeneous: public managers, entrepreneurs who create an app, service concessionaires, etc.

The methodology presented in this paper not only has been validated through two case studies, but also has been reviewed by 11 experts who gave their recommendations. As it was reviewed by both researchers and professionals, we can assume that it can be applied both in the scientific and the professional fields. The validation through two case studies proves the applicability of the method to various different business models; in fact, it has been explicitly conceived to fit the different use cases. The Evaluation Tool is not only open to modifications to be adapted to all smart cities. In fact, this measurement methodology could also be applied to business models of other areas such as regional, national and international public administrations; NGOs; and even other for-profit organizations fully aware of the development of the communities where they operate.

6. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Work

New technologies open the door to innovative business models applied to public services offered in smart cities. This article addresses the growing need of assessing and comparing potential business models through a new method called the Business Model Evaluation Tool for Smart Cities. This method allows choosing the most appropriate one depending on the objectives of each city.

Any stakeholder may be interested in evaluating the most suitable business model for a public service of the smart city. Therefore, we have designed a methodology that any stakeholder can use. The fact that it has been reviewed by scientists and practitioners proves that it can be used by both communities. In addition, it is based on the Business Model, the most used framework for analyzing business models, which should facilitate its adoption.

The Business Model Evaluation Tool for Smart Cities is an organized and transparent system that facilitates the work of the evaluators of potential business models. The methodology is flexible enough to collect all the factors that may affect the business models of utilities used in smart cities and be adapted to the specific needs of each of these strategies. For its rapid implementation, this method allows to measure and compare two or more business models and make strategic decisions swiftly.

Forecasting future performance of a business models requires a subjective component and, thus, the Evaluation Tool lead to debatable decisions. Nevertheless, it facilitates decision making and enhances transparency and accountability.

This method has been designed specifically for smart cities; however, it could be adapted to assess business models of other areas such as public administrations of any level or even for-profit organizations which feel responsible for the development of the communities where they operate.

In order to design this methodology, we have developed constructive research with a heterogeneous mix of complementary methods: content analysis, in-depth interviews to 11 practitioners and researchers, and two case studies to validate the framework.

To conclude, the authors must point out that in spite of the extensive research work developed; this study has a few limitations: It would be convenient to validate the Evaluation Tool through various different case studies and interviewing more researchers and practitioners. Both issues will be addressed in future works.

Acknowledgments

We thank to the European Commission’s H2020 Program, Organicity, GA-645198, for partially funding the research work carried out in this paper.

Author Contributions

R.D.-D., L.M. and D.P.-G. conceived and designed the experiments; R.D.-D. performed the experiments; R.D.-D. analyzed the data; R.D.-D., L.M. and D.P.-G. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; R.D.-D. wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

video refrence balanced scorecard strategy

References

- Popescu, R.I. Study regarding the ways of measuring cities competitiveness. Econ. Ser. Manag. 2011, 14, 288–303. [Google Scholar]

- Angel, S.; Parent, J.; Civco, D.L.; Blei, A.M. Making Room for a Planet of Cities; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 1–77. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Urban Planning for City Leaders, 2nd ed.; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2013; p. 187. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, S.; Marvin, S. Planning cyber-cities? Integrating telecommunications into urban planning. Town Plan. Rev. 1999, 70, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITU-T Focus Group on Smart Sustainable Cities. Master Plan for Smart Sustainable Cities; ITU: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, C.; Donnelly, I.A. A theory of smart cities. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the ISSS, Hull, UK, 17–21 July 2011; pp. 1–15.

- Walravens, N.; Ballon, P. Platform Business Models for Smart Cities: From Control and Value to Governance and Public Value. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2013, 51, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, O.; Navío, J.; Pérez de Heredia, M. ¿Cómo se Gobiernan las Ciudades? Silva Editorial: Tarragona, Spain, 2015; p. 118. [Google Scholar]

- Komninos, N.; Tsarchopoulos, P.; Kakderi, C. New Services Design for Smart Cities: A Planning Roadmap for User-Driven Innovation. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM International Workshop on Wireless and Mobile Technologies for Smart Cities, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 11 August 2011; pp. 29–38.

- Prof. Dr. Ir. Hapzi Ali, MM, CMA

Komentar

Posting Komentar